By Sujeet Rajan

NY Dosas has six signature items on its vegetarian menu all cooked by Thiru Kumar himself, a legendary Tamil chef from Sri Lanka. They include Pondicherry dosa and mixed vegetable uthappam, with accompanying spicy chutneys and savory sambar that leaves one craving to eat some more.

Semma is an upscale, award-winning Indian restaurant, with a Michelin star, which The New York Times rated as the second-best restaurant in the Big Apple. The prices of items on its menu are three times to 10 times more than those at NY Dosas, a nondescript, worn-out looking food cart, with one griddle, which is pushed to and from its location by its chef along with a helper, every day it opens its shutters.

Semma’s owners, renowned restaurateurs Roni Mazumdar and Chintan Pandya, known for the Dhamaka and Adda restaurants, along with chef Vijay Kumar, who is originally from Madurai, in Tamil Nadu, are established celebrities in New York City. The trio host and/or attend myriad glittering parties every month, following their runaway success with the opening of several restaurants, offering a twist on Indian food.

Prior to establishing Semma, Pandya and Mazumdar had gained recognition with the James Beard award-winning Dhamaka in Essex Market, followed by the opening of Adda Indian Canteen in Queens. Semma opened its doors in October 2020. Their latest venture, Masalawala and Sons, is located in Park Slope, Brooklyn.

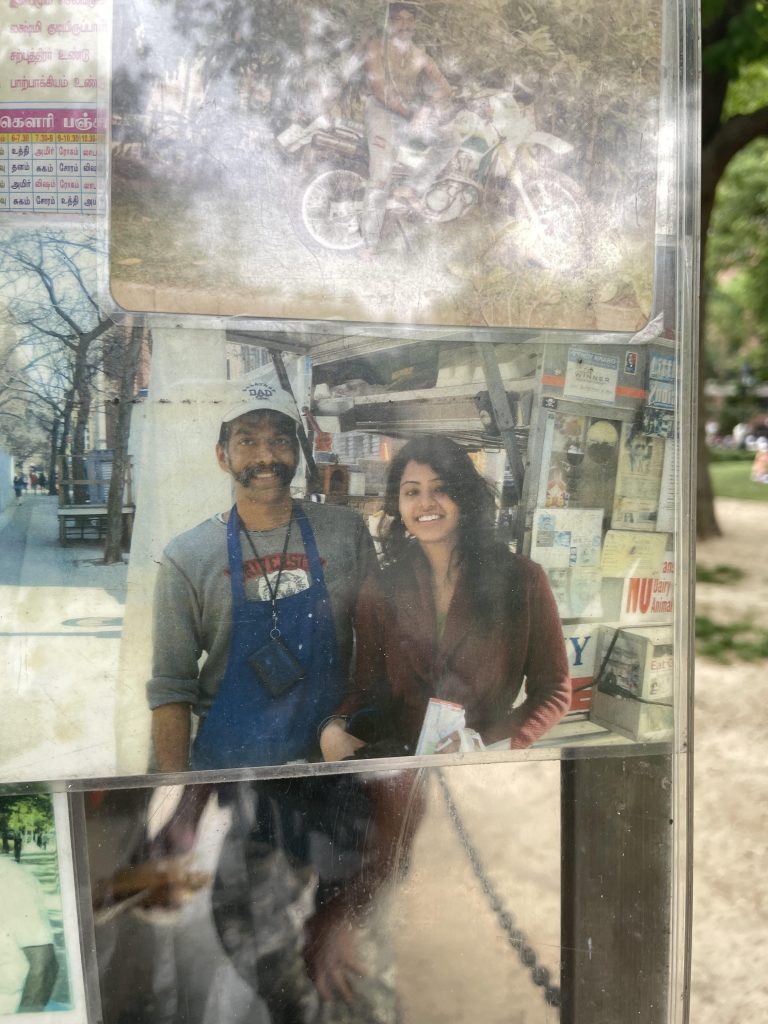

Kumar, who emigrated to the United States from Sri Lanka in 1995, is the owner and chef of the food cart NY Dosas. After doing several jobs, including working at a gas station, he launched NY Dosas in 2001. On most days he serves a few hundred customers, remarkably cooking the dosas himself. His effusive energy and enthusiasm are even more astonishing. Most customers demand a selfie with him, which he accepts with delight.

He eats lunch only after serving as many customers as he is able to for the day, once batter for his dishes runs out. He has a staple diet for lunch: a masala dosa, which he eats hunched over a small stool, as pedestrians walk past him, at his spot opposite the New York University campus. He gets up at 3 AM every day and will practice yoga before heading off to work. He goes to bed past 10 PM. He hasn’t attended a single party in his 21 years of business, he told me, except for the rare occasion when feted at family gatherings. He also has a vast fan base around the world. NY Dosas is listed in guidebooks in almost 50 countries, and has fan clubs in Japan, like some Indian film actors. In 2007, he won the Vendy Award for the best street food cart vendor in New York City.

In an interview with him, I mentioned Semma to Kumar, asked if he had heard of it or had gotten a chance to visit it.

Kumar responded: “What’s Semma? I’ve never heard of it. Probably they have come and eaten my dosas. I don’t have time to go there. The only South Indian restaurants I’ve visited are near home where I live, in Oyster Bay, Long Island. Or when I travel back to Sri Lanka.”

Despite their disparate standing in the Big Apple’s gastronomy scene, Semma and NY Dosas share something in common: an agonizing wait for their food, or, as it happens every day, the many disappointed who walk away without having tasted a morsel of their culinary offerings. It’s almost impossible to get a reservation at Semma – the wait can be weeks long, unless you know somebody at the restaurant, to propel you through its doors. And woe to those who show up late for lunch at NY Dosas. Most days, there can be anywhere from 100 to 200 people in a line that stretches and winds past chess players on benches and children and dogs playing in Washington Square Park.

Some people come to NY Dosas at 8 AM, to get at the head of line for the opening call for orders, which most days is at 9:30 AM. Every day, Kumar gauges what the situation will be by early afternoon, when the batter for the dosas might run out, and places a cooler to mark the “cut-off” point to the queue and requests the client who stands at the cooler to inform those who come after that there will be no dosas for them. It is useless to stand in line. Some of the chess players call out, reiterating Kumar’s words to those who come late.

On a recent weekend, I was that last person to get on the line and Kumar gave me the onerous duty to pass on the devastating news to dozens of people who arrived after me – some had traveled from different countries, some from other states – to get a taste of NY Dosas: “Hey, sorry, today’s not going to be that day.”

Kumar relented at times. He was kind to a woman who came with a baby in a stroller and let her come to the front of the line. Two couples and their children from West Virginia, originally from Andhra Pradesh, decided to take a chance, and stood in line behind me. I was glad to hand over to them my responsibility of giving the bad news to others. I asked them if they were alright to wait for so long for a dosa, which could be had without too much of a wait at Saravanaa Bhavan restaurant, on Lexington Avenue.

“She has told me she wants to eat only at Dosa Man, in New York, so we are not going back without eating here,” one of the male members said, as his wife laughed along. She said: “I’ve heard so much about him. Last time we visited we couldn’t get to eat here. This time, I’m determined to eat a dosa here.”

Nostalgia, and a craving for that near perfect rousing meal that conjures up memories of a golden past or creates new memories is what drives some people to scout for a particular cuisine when they visit cities. There’s a popular belief that there are seven doppelgangers of oneself in the world. So, it stands to reason that a mother’s cooking must have a few replicas out there.

For a gourmand, food that appeals to their cravings blurs and often obliterates the lines between eating on silverware at a fancy, expensive restaurant, or devouring with relish piquant food from a plastic tray, standing near a food cart on a busy street, oblivious to passersby who stare with fascination as they walk past. The venue is a moot point.

As Virginia Woolf aptly put it: “One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well.” It is the taste and quality of food that sustains a business. Without it, businesses are forced to close shop. It is the reason why a visiting Indian family from West Virginia – like dozens of others like them – stand in line for hours to eat a dosa from a street cart at a nondescript location in New York City. They’re hoping to lock in a happy memory for years to come, goad others to follow the route they took.

I got into line at NY Dosas on a Saturday at 1 PM, with dozens of people in front of me. I finally got a dosa in hand past 4:30 PM. Soon after Kumar designated me as the last person to be served, a young woman from New Jersey, originally from Rajasthan, came up to me and requested to please buy a dosa for her too. She said she would pay me. I told her that since she was the first to request from me something so novel and profound, I had no choice but to relent to her demands. We shared some good conversation, and laughter, while waiting in line. She was a real foodie and shared her knowledge about lesser-known good eating spots in the city. She got her dosa before me.

It wasn’t too bad standing in line, with a healthy dose of banter with those in line, and newcomers who came along every few minutes. The only other time I’ve waited that patiently for something in New York City, was to watch live the ball drop at midnight at Times Square, at a New Year’s Eve two decades ago.

Kumar says he stopped doing the food cart business only for money years ago, after his fan base grew globally.

“I’m not cooking only for money. I do it for love, for the people who visit me every day. I’ve always wanted to do something different, and this is what I like doing, something nobody else is doing,” Kumar said, in the interview to India Overseas Report.

After a former NYU student comes and gives him a hug, and told him he missed his cuisine, I asked Kumar about the effect of Covid on his business, and if during the time he got off from work, did he think to do something else in life.

“During Covid, I stayed home for six months, spent time with family. I got to spend time with my daughter, who graduated from Columbia University, and is now working. It was a good time for me personally. I started work after NYU opened and I got calls from students and staff who wanted me back. I went back, and haven’t stopped since then,” he said.

Kumar says he’s never wanted to start a restaurant of his own, as he wants to provide quality food at a cheaper price for everybody.

“I got my love for cooking from my grandmother, when I was growing up in Sri Lanka,” he said.

He doesn’t reveal his age or income, but when asked if he has a timeline to retire, he says, “Never, well, not right now. I will go on till 2029, and then see if I get all the licenses renewed. If not, then I will shift to some other place from here.”

A dosa? What is all the fuss about?

For the uninitiated, a dosa is a thin crepe, or a pancake, made from fermented batter of ground black lentils and rice. They are a staple in South India, used as a dish on its own, or stuffed with vegetables or meat, used as a canapé too. Some come larger in size than the plate it’s served on, shaped like a tube or gargantuan pyramid.

The origination of dosa has been debated. Historian P. Thankappan Nair claims its birthplace is in Udupi, Karnataka. Food historian K. T. Achaya says dosa was a concoction from 1st century CE, in Tamil Nadu, before it showed up in Karnataka.

Kumar told me that he ferments his dosa naturally, uses a ‘old school’ stone grinder, and that all ingredients are hand-picked, and made in a commissary daily. It’s as healthy a vegetarian meal as can be, he added.

“It’s full of protein, that’s all one needs,” he assured me, as he ate his lunch, after he watched me eat an “off-menu” dosa and uthappam he cooked for me.

Wheels vs brick and mortar

The rivalry between restaurants and food carts is decades long, in New York City.

“The fight between brick-and-mortar restaurants and food carts is covered heavily in the media today, but it’s old news in this town,” reported Eater. “In 1906, the mayor’s ‘Pushcart Commission’ looked into the ‘evils’ of street vending. The issues ranged from the familiar — street crowding and “additional odors and noise” — to more pointed criticisms like the fact that “this occupation without special qualifications” attracted additional immigrants to New York City. But even the fears of an expanding immigrant population were likely swayed during lunchtime. In a pre-refrigerator age, outdoor food carts and fruit stands were an extension of many urban kitchens, and the commission’s “investigation goes to show that there is no special danger to the community from the food supplies sold from pushcarts, for the wares are usually as good, if not better, than the supplies sold in neighboring stores.”

Although the numbers vary, according to a report in NBC New York from November, 2019, there are roughly 130 mobile food vending commissaries and more than 5,000 food carts registered in New York City.

Mobile Food News, in a report over a decade ago noted that there were as many as 25,000 food vendors roaming the streets of the Big Apple. They included fruit vendors (known as Greencarts), coffee carts, halal food carts (which conforms to Muslim religion’s meat leniency) that sell Middle Eastern and Indian food, hot dog vendors, ice cream vendors, and cuisine-based vendors.

Eater in a separate report on halal carts – which first began popping up in the late 1980s, cited a 2007 New York Times article which reported that a Queens College sociology study indicated that between 1990 and 2005, the number of food vendors who self-identified as being of Egyptian, Bangladeshi, or Afghan descent “surged to 563.”

The Institute for Justice noted that by 2011, food trucks were the fastest growing sector of the restaurant industry in New York City, after their resurgence during the recession from couple of years earlier. Some observers thought food trucks were a flash in the pan, but the public saw things differently: A study revealed that 91% of consumers familiar with food trucks thought trucks were here to stay. Many successful food trucks have, like Kogi, spun off their own brick-and-mortar restaurants. Examples include Curry Up Now, which started as an Indian food truck in San Francisco in 2009 and now has 18 brick-and-mortar locations across the country, the report said.

Indian cuisine reaches America

Indian cuisine has a long trajectory in this country.

Siddhartha Vaidyanathan, writing in The Wall Street Journal in 2010, featured Alamgeer Elahi, an Indian immigrant from Kolkata, who had a food cart on Fifth Avenue. His yellow van was plastered with posters of Bollywood stars.

Post the 1965 immigrant surge, Indian restaurants started in New York City with launch of Raga by the Taj group in the 1970s, which is now closed. Sant Chatwal opened Bombay Palace with great success in 1979, and later ventured into the hotel industry.

However, the Indian food revolution started much before in New York City.

Several academic reports note that the first Indian chef in North America, J. Ranji Smile, left the Savoy Hotel in London in1899 to take up a job at the Hotel Sherry’s Restaurant in New York, “initiating the fashionable set in New York into the mysteries and delights of East Indian cooking,” according to a report in Harper’s Bazaar.

Anita Mannur, Assistant Professor of English and Asian/Asian American Studies at Miami University, whose book, Culinary Fictions: Food in South Asian Diasporic Culture – one of the first full-length studies of food in the South Asian diasporic cultural imagination, writing in the South Asian American Digital Archive, noted an Indian restaurant was discovered on Eight Avenue near Forth-second Street, in the early 1920s. The restaurant was the Taj Mahal Hindu Restaurant located at 243 W. 42nd Street.

Academic Vivek Bald noted that only four blocks to the west of the Eight Avenue Boarding house were, “two of the first Indian restaurants in the city, which were four blocks south: the Ceylon Restaurant (est. 1913) on Eighth Avenue at Forty-Third Street and the Taj Mahal Hindu Restaurant (est. 1918) on Forty-Third Street between Ninth and Tenth Avenues, as well as to the Ceylon India Inn, an expansion of the Eighth Avenue Ceylon which was opened in 1923 nearby on West Forty-Ninth Street.”

The cultural historian Jayanta Sengupta, wrote that following the loss of the East India Company’s India monopoly in 1813, Indian spices became more easily accessible to the middle classes, especially in New England, as indicated by the emergence of chicken curry, curried veal and lobster curry as standard items dished out by taverns and eateries in Boston, in the first decades of the nineteenth century. Significantly, recipes for a chicken curry “after the East Indian manner,” for a similarly spiced catfish curry and for curry powder were included in a pioneering American cookbook, Mary Randolph’s The Virginia Housewife, or Methodical Cook, as early as 1824.

Don’t mess with nostalgia

If food deviates too much from what a specific type of cuisine should ideally taste and be cooked like, then the cause célèbre of immigrant angst, often found in the reminiscing of home cooked or favorite food hangouts from days gone by, becomes more pronounced. There are countless deliberations on the merits and demerits of experimental cuisine, in the name of serving Indian food.

A line from ‘In a blue time’, a short story by Hanif Kureishi: ‘This was delicious, but also a provocation, mocking justice’ – even though out of context from the subject matter in the fiction – could aptly describe popular, but underwhelming Indian food cooked at too many mediocre restaurants, in the Tristate area. Some Indian food is most palatable after one is hungry for hours; eaten with a voracious appetite, with scant regard for taste buds, or critical appraisal. Or perhaps, its aberrations in mixture of ingredients and cooking, are camouflaged by the aura of an alcoholic drink too many.

The lingering aftertaste of some dishes considered as being too oily, not being spicy enough, undercooked/overcooked, or absurd experimentations, emanates afterwards for gourmands who like satisfaction as much as satiety in every concoction of a meal.

In search of more Indian fare

That evening after I took leave of Kumar, I went to Fifth Avenue near Times Square where another food cart was serving Indian food: Biryani Cart, which is operated by Aminul Islam, a Bangladeshi immigrant. He has been running the cart for 14 years, at the same location. Unlike the scene at NY Dosas, during the time I spent with him, only two customers came for a pack of biryani. A homeless man lounged about nearby, cajoled and harangued customers to offer him some food.

Although I had plans to meet some people for dinner later that evening, I decided to taste a bit of Islam’s cooking. I got a chicken biryani packed, and then ate some of it in Times Square, as I watched some youth dance and do acrobatic moves.

Islam, who worked at a rice mill in Dhaka before he left for the shores of America, started the cart soon after he landed. It was his first job in America once he had his license in place. He usually comes in at 5 PM, and leaves for home at 9 PM, and has workers who help take care of his business at other hours.

“I never wanted my own restaurant, as this was doing well. Now, business has been slow, with many offices open but a lot of workers not coming in all the days of the week,” he said.

Despite all the great food on his truck, Islam savors home cooking. “At home, my wife cooks for me, and I like rice, with fish curry and goat,” he said.

As I people watched in Times Square, some people sauntered by holding hot dogs and pizza slices, eating as they walked, definitely a New York tradition. This brought to mind a curious sight from earlier in the day: while waiting in the line for Kumar’s dosa, some people were eating pizza. They had come to have a dosa for lunch; ended up getting one closer to dinner time, with pizza in between the wait.

Last week, my wife and I ate lunch at Madurai South Indian Cuisine restaurant, in Stamford, CT, which is in the same premises as Tawa restaurant. While the Mysore masala dosa and sambar vada which we ordered was below par, I ate with relish a plate of fish Koliwada made from sea bass, cooked in the style popular in restaurants in Maharashtra. I’m used to this by now in Indian restaurants who have dozens of items listed on their menu: go to eat a specific item thinking it’s their specialty, but end up liking something totally different.

Also last week, on way to a grill in Westport, CT, somebody queried if I liked escargot, or cooked snails, considered a French delicacy. I was emphatic in my answer: ‘No’. Cooked snails, however, at Semma, have gotten rave reviews.

The fusion of traditional Indian cuisine with modern twists may to some be a stark, unpalatable contrast. It’s perhaps like listening at home to a mellifluous raga by violinist L Subramaniam at night, with the harsh trilling of cicadas forming a hoarse chorus in the background. For some, though, it’s exciting, exotic sounds.

Some of my favorite Indian and South Asian restaurants in the Tristate area, outside of New York City, are Korai Kitchen in Jersey City, NJ (read my review of Korai Kitchen), Coromandel, in Darien, CT, and The Naan, in Westport, CT. Authentic and creative, these restaurants share the one sure fire mantra that never fails to appease repeat customers: high quality, delicious food that doesn’t make one feel guilty or remorseful after overindulging.

(Sujeet Rajan is Editor-in-Chief of www.indiaoverseasreport.com Follow him on Twitter @SujeetRajan1)

(This story was produced as part of the Small Business Reporting Fellowship, organized by the Center for Community Media and funded by the NYC Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment.)