By Sujeet Rajan

When it was put in the market, it drew a frenetic response from young men who were desperately searching for any job to pull themselves out of the Great Depression.

A total of roughly 16,900 medallions were sold, but in the throes of a financially ravaged society – when enough commuters couldn’t afford to pay for a ride – that number dwindled to 11,787 as thousands of cabbies couldn’t renew their annual $10 medallion license fee.

Bruce Schaller, the director of policy development at the Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC) from 1986 to 1994, told The New York Times that after the stock market crash in 1929, by 1930, job seekers swelled the ranks of New York City cabdrivers to 30,000.

The medallion was introduced to curb the number of drivers who could legally operate cabs; to make it a profitable venture. Some cabbies worked 20-hour days and were unable to make an adequate living, said Schaller.

By 1950, however, as the economy rebounded after the end of the second World War, the price of a medallion escalated to $5,000. In 2013, the value had tripled from the 2005 price of $325,000. It rose to a dizzying $1.3 million in 2014, as investors rushed in to take advantage of low interest rates on loans.

The advent of Uber in 2011, and later Lyft in 2014, however, began to erode the medallion’s value; decimated it. The website Documented noted that while city authorities limited yellow taxis at 13,500 in 2014, there were no such curbs on the proliferation of app-based rideshare vehicles: their numbers tripled between 2010 and 2019, from 40,000 vehicles to over 120,000.

The speculative bubble that built around medallions burst and exploded into smithereens around 2018.

The TLC had earlier introduced an extra 1,000 medallions to scoop up revenue for the city. That move backfired to the detriment of the medallion owners, as demand ceased. The onset of the Covid pandemic in 2020 exacerbated the decline. In September of 2021, the price of a medallion reportedly sunk as low as $65,000-$80,000.

Today, there are about 13,500 medallion taxis in New York City. While they are allowed to pick up fares all over the city, and NYC airports, they used to have sole rights of customers in Manhattan below 110th Street, before the ridesharing cabs too joined in, changing the scenario in a drastic way.

Drivers who lease a medallion taxi are considered independent contractors and are liable for all expenses. They get to take home only what they make minus the money they paid to lease the vehicle for a shift, which is sometimes 12 hours.

For Karnail Singh, 65, a yellow taxi driver in New York City, the initial few months of the 15 months he was forced to sit at home because of the lockdown effect of Covid, was a terrible time in his life. He couldn’t work as the pandemic ran rampant and destroyed people’s lives and their livelihoods by the tens of thousands, in 2020-2021.

It was even worse than the time in 2018 when Singh was forced to give up his once-coveted medallion. He had to declare bankruptcy to save himself and his family from financial perdition.

Five years before, in 2013, the growing competition from Uber and Lyft drivers seemed to swoop down like a marauding army. They snapped up rides at cheaper rates in every conceivable hour shift, devastating Singh’s income, dropping it to unsustainable levels.

Despite working 10-hour-long shifts seven days a week, he couldn’t keep up with his monthly payments to cover even basic living expenses, or, put enough food on the table.

Singh’s $341,000 debt from the medallion he bought in 2004 grew at an alarming rate; monthly payments ballooned. Its actual price fell to less than 50% of its value in 2018. His morale sank; he was devastated mentally.

The loss in value of the medallion dealt a death blow to the hopes of drivers like Singh, of an early retirement. It made a mockery of his American Dream of enjoying a windfall from his investment, once considered as solid as a blue-chip stock or buying an apartment in New York City, with steady dividends and escalating value.

The medallion had on the contrary become a curse, a financial sinkhole. It threatened to suck him and his family to depths of homelessness. He and his son succumbed to the dire situation, and called it quits.

As the rest of the world were celebrating some of the comforts of advance of technology – getting food delivered on an app, eating in, riding a cab booked on an app – for taxi drivers like Singh, it was just technology gone rogue.

His younger son, who was around 25 years old at that time, capitulated to the stranglehold of debt. He too was forced to give up his taxi medallion. Singh and his son declared bankruptcy, in 2018. They were forced to give the medallion back to the bank, which had given them loan for it.

Ironically, 2018 also was the worst year for stocks in 10 years, provoking a financial crisis. In December of that year, the S&P 500 fell more than 9%, marking it the worst December since 1931, harking back to the days of the Great Depression.

“Those were just really bad days, but even then, I didn’t think of going back to Punjab,” reminisced Singh, in an interview with India Overseas Report, at Lexington Avenue, between 28th and 29th Street.

He often parks in that relief area for taxi drivers, to grab lunch from one of the several Indian eateries in the vicinity, he disclosed.

With his long, white beard on a wizened face, soft voice and smiling demeanor, Singh seemed more like a genial priest at a local gurudwara than a hardened taxi driver in a city that truly never sleeps.

I asked him if he wanted to eat first and then give me some time for a conversation. It was 2:30 PM. He asked me with a smile if I was hungry. I told him I’d already eaten. He told me he was in no rush to eat. We carried on our conversation.

“During Covid, I was perplexed. I felt lost. My three sons didn’t know what to do. I seriously thought of going back with my family to Punjab after 18 years of driving a taxi in New York,” he said, changing from English to Hindi frequently, as he spoke, his body still, hands by his sides.

“Manhattan was like a ghost town. Nobody wanted to venture out. There was no question of driving anybody anywhere. People were dying. I thought that following my loss of the medallion in 2018, Covid would be my end. Tragedy was hounding me and my family. I didn’t want to stay home, was desperate to drive, make some money. But just when I thought everything was lost, the government gave help. I got money from unemployment. I survived because of help from the government. My hope was renewed. I’m grateful for that help,” he said.

Nowadays, Singh is driving a medallion taxi on lease from a garage.

“I drive 10 AM to 7 PM seven days a week, with a break for lunch,” he said. “I like driving, so it doesn’t bother me. I’m happy to go back every evening to my family.”

Singh lives with his three sons, two daughters-in-law, and two grandchildren, in a single-family house in Valley Stream, in Long Island.

“After all expenses I make around $500-$600 a week,” he said.

Asked if that money was adequate for all his hard work, and sometimes the subtle and overt racial taunts he gets from callous customers for his appearance and skin color, he philosophized: “It’s not just competition from Uber and Lyft. There’s inflation, the economy is in the doldrums, what can I do? I’ve learnt to accept situations and make the best of it.”

He shook his head when I asked him if he would recommend youngsters to become taxi drivers, in New York City.

“Never”, he said emphatically. “I’ll not recommend this job to the younger generation. They should study in college, get a job, or do some other business. Taxi’s future is not bright.”

Despite the roller coaster of a ride the value of a taxi medallion has had in the last 10 years, with its financial pitfalls and dubious unpredictability, there are still takers for it, in New York City.

In an interview, Mohammed Khalil, 56, who emigrated from Bangladesh, and has been driving a taxi for the last 14 years in New York, said he was encouraged by the fact that the government helped him “survive Covid.” He thought that with that adversity behind him, the worst was over. A medallion would again rise in value, despite the competition from Uber and Lyft, he reckoned.

“I didn’t drive for six months during Covid as I took unemployment. Later, I got a job at a pharmaceutical company, worked there for about a year, and then came back to driving a taxi. I got my medallion late last year for $140,000, with a partner,” he said.

Khalil praised profusely the New York state and federal government for helping taxi drivers like him during the Covid crisis, which he felt saved him and his family from total financial disaster.

“I came from a Third World country so I can say thank you! to this country. We got some benefits and unemployment from the government, and it really helped me and my family at a time we needed it the most. Covid was not too bad after all. I was able to take care of my family as we did not go out that much. We just used money for food. My kids were at home, so expenses were kept low,” he said, in the interview conducted during his lunch break.

Khalil said that with a medallion he’s able to better structure his work hours, while making more money than he would working for an employer.

“Still there is risk about the medallion despite the price of the medallion going up slightly in the last few months. During Covid time it was around $65,000 to $90,000. Today, it’s around $140,000-$190,000,” he revealed.

Khalil leaves his home in Jamaica, Queens, at 5 AM and works till 5 PM. “Some days, I do 7 AM to 5 PM,” he said.

Khalil said if he works 10 hours a day, for six days a week, he makes around $4,000 a month after expenses. He’s taken a 15-year loan for the taxi medallion for which he pays $115 every week in mortgage.

Despite recent price hikes in yellow taxi fares in New York City, raising the base and per 1/5th of a mile driven, and debt restructuring for some drivers with medallion debt, Khalil echoes Singh’s sentiment when he advocates youngsters not to join the taxi driving profession.

“I think for us older folks, it’s not bad, but for new generation they should go to school and get a good job. For new generation, perhaps it’s ok to do a bit of driving, make some money for college and then leave it,” he said. “There is big competition from Uber and Lyft. That’s not going to end.”

He makes it clear that he doesn’t recommend driving a car for an app ride-hailing company either.

“If somebody hires my cab from here to Jamaica (Queens), it would be around $45. Uber might be around $30. So, it’s good for customers, perhaps. But Uber drivers have to drive much longer daily to make more money than a yellow taxi, as the Uber company takes a lot of their money,” he explained.

In interviews with several yellow taxi drivers, it became apparent that drivers make a startlingly different amount from their service, despite the shadow of Covid and its ill effect still hovering around, creating unease and uncertainty. For most though, apart from competition posed by ridesharing companies, they also face competition from the TLC-sanctioned Green cabs, which operate only in the boroughs.

A dearth of riders in Manhattan in the wake of the pandemic has also hit yellow taxi drivers hard.

New York City’s economy is still reeling with plenty of near empty offices in the aftermath of the work from home policy which many companies have now almost made permanent. The lesser number of office goers, especially, has had a debilitating effect on several industries, including restaurants. Taxi drivers have been hit as hard as any other industry.

Not so for K Maniruzzaman, though, who lives in the Bronx. He emigrated from Bangladesh and has been driving a taxi for the last 12 years. He bought a medallion in 2019 for $185,000. He managed to keep his head high despite the Covid-imposed lockdown, and now, he said in an interview, he is making good money.

“Covid was a hard time because I had to take care of not just myself, but my family members too. My wife’s parents, my father-in-law and mother-in-law are living with us. It was really hard for us as we heard news almost daily that somebody we knew had died of Covid,” Maniruzzaman said.

“However, I couldn’t survive without working, so six months after Covid started I started to drive again. I did get unemployment and a PPE loan, so that really helped me, but I had to work hard to make ends meet,” he said.

Maniruzzaman said he doesn’t qualify for loan restructuring introduced by New York City authorities recently, for his medallion debt since he took a cash loan from a source other than the TLC or their affiliated brokers. He won’t be eligible for a $30,000 debt forgiveness from the City, either, for his medallion.

He says in the past he worked for Uber for two weeks and never liked working for it.

“Uber takes money from their drivers. The driver doesn’t make much money,” he said.

There’s an advertisement flashing on top of Maniruzzaman’s taxi. It’s an Uber ad, almost as ubiquitous as those promoting flash dancers in adult clubs.

When I pointed out the irony to him, he laughed, and said it supplements his income.

“I make around $3000 a week in total from driving, and after expenses, I take home around $2,500 a week,” he said. “Driving a taxi is a smart choice for youngsters if you want to make money quickly. But I would say to try to drive a yellow taxi. Don’t become an Uber or Lyft driver.”

Debt Restructuring

Debt restructuring was a major victory for many impoverished taxi drivers with a medallion and for several advocates, including the New York Taxi Workers Alliance (NYTWA), a union, who even undertook a fruitful sit-down protest across City Hall, last year. Since the struggle for debt restructuring began years ago, several taxi drivers who were financially ruined by the burden of their medallion, committed suicide.

Last month, New York City Mayor Eric Adams, New York City TLC Chair David Do, and U.S. Senator Charles Schumer announced that the city’s taxi Medallion Relief Program (MRP) has successfully provided more than $350 million in debt relief to medallion owners since the program launched in September 2022 — restructuring loans for nearly 1,800 struggling medallion owners. As of January 17, 2023, $356 million in debt has been forgiven on 1,789 medallions.

Since the initial agreement with Marblegate Asset Management, a hedge fund based in Greenwich, CT, TLC has reached agreements with additional partners — including Pentagon Federal Credit Union — to deliver debt relief for medallion owners in their portfolio.

Under MRP, principal loan balances have been reduced to $170,000 from balances as high as $750,000. Monthly payments, in turn, are capped at $1,234 — down from an average monthly payment of $2,200.

“More than $350 million of awarded debt relief is more than a number — it represents a new life for nearly 1,800 individual medallion owners who, after years of serving the public, found themselves unable to pay for the basic costs of their profession,” Deputy Mayor for Operations Meera Joshi, said, in a press release. “…New York City’s iconic yellow cabs and even more iconic cab drivers are once again up and down our avenues and streets keeping New York City on the move.”

For Marblegate Asset Management, the debt restructuring is still a winning proposition. In 2018, they bought 3,000 medallion loans for $110,000 each from lenders, making money off the misery of drivers who were stuck with high debt.

A taxi driver from India, who stays in Queens said, under the condition of anonymity, that he’s applied for debt restructuring for his over $300,000 loan balance.

“I’ve always had faith in America. I got help during Covid from the government and now the government is helping again. I’m really happy that finally taxi drivers too are getting help when we really need it,” he said.

Organizing and Advocacy

I took a subway train to the NYTWA office in Long Island City, to try get an interview with its executive director, Bhairavi Desai, one of the most famous of Indian American activists in New York City.

Desai has advocated for the welfare of taxi drivers in New York City for close to three decades. I had sent phone and email requests without getting any response from her office. I thought some guerilla-style effort might help get a few minutes with her. Desai was absent that day.

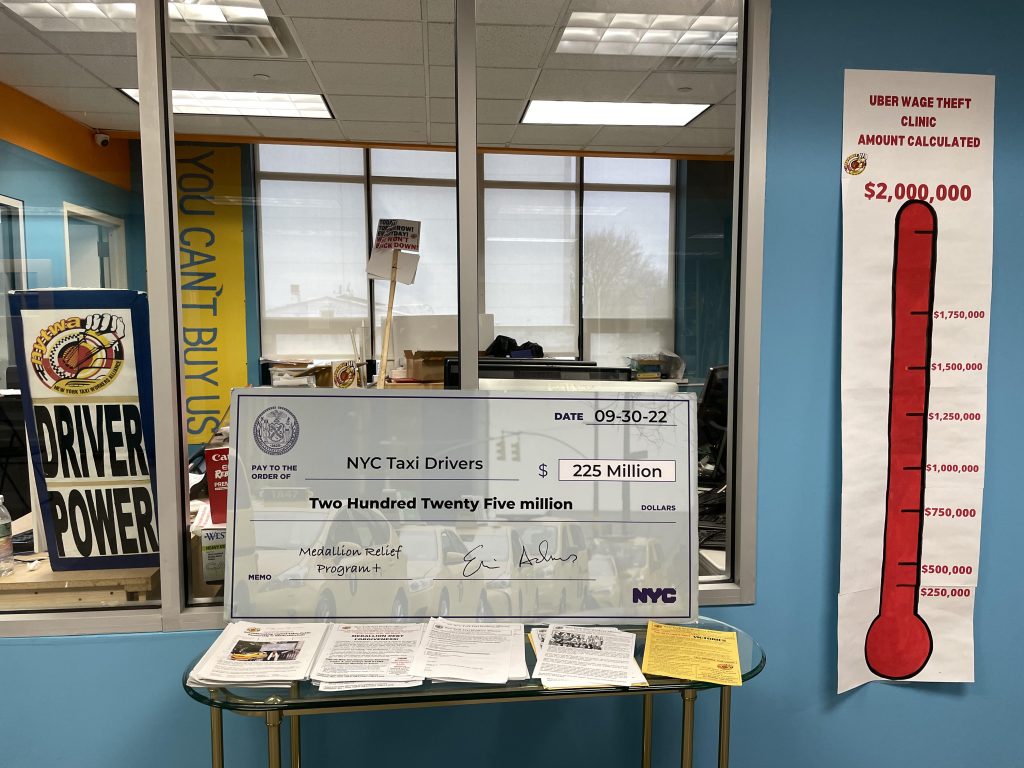

In the office, only two workers were present, when I visited. In the capacious office, an enlarged cardboard check – a la lottery-style for winners – was displayed prominently. It’s signed by Mayor Adams, for the sum of $225 million made out to NYC Taxi Drivers – the amount given for debt restructuring of medallion holders. It’s dated from September of last year. A separate area had empty chairs in neat tows, presumably for addressing workers, prepping them for foreseeable union action.

There’s also a large poster which says in two lines: ‘DO NOT FEAR – ORGANIZE.’ There are shoals of fishes depicted on it for pictorial effect. The underlying message is clear: if smaller fish organize efficiently, cohesively, then bigger sharks beware.

However, for all their fine effort, the task of NYTWA is one that would puzzle many nowadays. Not only do they advocate for the yellow taxi drivers, but are also striving to get wages increased for app-based drivers, including Uber and Lyft.

If they succeed, it could be to the detriment of the yellow cab drivers, as more app-based drivers could join the city’s already-bursting-to-the-seams taxi ranks.

It’s a grim scenario, reminiscent of the time in 1930 when there were too many cabbies on the roads of New York City. The likely outcome could be a no-win situation – for the union as well as the drivers, as further challenges crop up for drivers of all commercial cars.

Also, in several instances, the city, against whom NYTWA raised cudgels for decades, has now become a partner in their efforts: they sometimes work in tandem, like getting a wage hike for Uber and Lyft drivers.

TLC had earlier recommended a wage hike for app-based drivers in New York City. A court struck it down after Uber countered it successfully in court. However, a 9% raise is on the cards for those drivers as TLC will reportedly vote this week to implement it. NYTWA, on their part, had organized taxi workers’ strikes, most recently at La Guardia airport, last week.

While the union has had no choice but to try to widen their reach with tens of thousands of new drivers burgeoning the workforce, and to urge them to take the same $100/annual membership as it charges the yellow taxi drivers, it’s apparent to many analysts that there’s not enough space in NYC for all drivers to make a successful living off it. Something has got to give. It remains to be seen who goes out of business first, or at worst coexist with smaller income returns.

In NYTWA’s office, there are also copies of a feature story published in The Nation, in December of 2021 – ‘HOW THE TAXI WORKERS WON’ by Molly Crabapple.

I’m a fan of Crabapple’s wonderful writing and even more riveting original illustrations she draws, to accompany her text. I perused through the story as I waited to see if a staff member could reach Desai for me.

It was a blow-by-blow account of the strike over the span of several weeks, written almost like a miniature book, with a preface to the agitation that finally yielded startling results.

The sit-down strike by some taxi workers in September of 2020, was staged opposite the City Hall. NYTWA had announced the strike to force the city to fix the debt accrued by the medallions that had driven many drivers to suicide. Attempts over the years by the union to put a cap on monthly mortgage payments for beleaguered drivers, had been stymied by the NYC authorities.

Crabapple surmised: “The drivers’ victory was a testament to the unifying power of collective labor action. Ninety-four percent of cab drivers are immigrants, and 95 percent are men, but there are few other commonalities among them. Cabbies represent almost every race, religion, and country of origin, and they speak over 120 languages. They spend their days isolated in their cabs, competing for a dwindling number of fares. Yet for decades, NYTWA – a 21,000-member union of cab, livery, and rideshare drivers – had brought them together around their common plight. Now, through relentless work, shrewd organizing, and ferocious solidarity, cabbies had moved the city.”

Crabapple wrote of the plight of some of the workers at the sit-in strike, their last resort at breaking free from the shackles of debt from their medallion. A driver, Augustine Tang, inherited his father’s taxi medallion, along with $530,000 of debt; Mohammed Islam, from Bangladesh, owed $536,000, and “Big John” Asmah, from Ghana, owed $700,000.

Crabapple also noted the tragic suicides of some taxi drivers which had shocked the city, like Douglas Schifter, who parked his car outside the gates of City Hall and shot himself in the face.

In the suicide note he posted on Facebook, Schifter wrote that, after Uber entered New York, he needed to work 120 hours a week just to scrape by, and that fines, fees, and delays imposed by the TLC had left him deeply in debt. Other suicides followed: Nicanor Ochisor, 64, from Romania; 56-year-old Yu Mein “Kenny” Chow, from Burma; and 58-year-old Korean immigrant Roy Kim. In all, by the end of 2018, eight drivers had taken their life, wrote Crabapple.

Medallion taxi workers have come a long way from the vicious doldrums of living a life mired in debt, since then, especially with the debt restructuring announced by the city.

Present and Imminent Challenges

Over the past decade, no other profession in NYC has periodically had to face daunting odds like medallion taxi drivers.

These drivers have worked hard since they emigrated to the US. While most other immigrants, skilled or unskilled, started to build better lives and thrived, some of these migrant drivers discovered to their chagrin that despite playing by the rules, and a huge investment in a medallion, they were on the verge of or financially ruined. Their ambitions and hopes were shattered.

The precipitous downward spiral of a medallion price, fierce competition from app-based cab services and the devastating Covid pandemic appeared like a rock face. Many found it easier to stall on the road, leave their vehicle and run.

Despite the debt restructuring, ominous challenges for medallion taxi drivers to make a decent living are waiting in the wings. They can come raining down on them like unrelenting arrows from different directions.

On the horizon is congestion pricing in New York City to raise needed funds for transit infrastructure and reduce traffic. It will directly impact medallion drivers, who would have to fork out more on tolls when entering the congested areas of Midtown and Lower Manhattan – the bread-and-butter areas of these drivers. App-based drivers on the other hand, could pass the extra cost to customers, and still seem a better bargain.

The Gotham Gazette put out a study by Lucius Riccio, adjunct professor of statistics, analytics, and operations at NYU’s Stern School of Business. He found that 36.3% of 2,000 vehicles recorded in randomly selected Midtown locations were for-hire vehicles run by app-based companies like Uber and Lyft; and 14.2% were yellow or green cabs.

Riccio, a former DOT commissioner under Mayor David Dinkins, said his findings illustrate that for-hire vehicles are the real driver of traffic congestion in Midtown, and other parts of Manhattan too.

A 2018 study succinctly laid out the challenges to medallion cabs from app-based ones. Titled ‘New York City Taxis in an Uber World’, by Kristin Mammen and Hyoung Suk Shim – both Associate Professors at the CUNY College of Staten Island – the study took into account the effect of Uber’s presence on the demand for medallion taxi trips in New York City.

One of the key takeaways is that Uber rides replace, rather than supplement, medallion taxi trips during the morning rush hours in the central business district of Manhattan, below 110th Street. In the boroughs, Uber similarly supplants Green cabs during weekends, their study concluded.

While some medallion drivers like Singh and Khalil are content with money they make from driving, even if it’s less than past years, there are warning signs that more trouble is afoot through likely growing competition in the industry. It could put a further stranglehold on the economics of possessing a medallion; and spell its death knell.

NYC is planning to give out 1,000 for-hire vehicle licenses to drivers of electric cars, according to TLC. It’s the first time since 2018 that the city is issuing new licenses to for-hire vehicles, reported ny1.com. The 1,000 new licenses for electric vehicles will create more competition for taxi medallion owners in the city, the report noted. Details are not yet out, though.

In the boroughs, where Green cabs rule the roost, and medallion drivers do plenty of business too, the introduction of more Dollar Vans – a ‘shadow transit system’, in existence since the 1980s, which bridges the distance between areas far away from a subway or bus station for commuters, could further put a dent in the demand for car rides.

Bloomberg reported last week that Su Sanni, a Nigerian-American entrepreneur who grew up in Brooklyn and Queens, founded Dollaride, a startup that seeks to modernize this network, debuting with an app that allows riders to find and pay for rides.

With the help of a $10 million grant awarded by New York State Energy Research and Development Authority last fall, part of the larger New York Clean Transportation Prize competition, Sanni hopes to put a fleet of 60 to 70 of these low-cost vehicles, similar to tuk-tuk vehicles found in parts of Asia, over the next two years.

It remains to be seen how many cabs would go out of business if Sanni’s venture takes off successfully; or alternately, be forced to do with less as their territory for fares diminish.

Club for Cab Drivers

In these tough economic times, even when a seemingly grandiose and unique gesture is made to these beleaguered medallion taxi drivers, it comes with a pinch of irony, and anomaly.

Take for example a new Taxi Club that opened in the Chelsea area of Manhattan, last month.

A visit to the club gave a glimpse of impressive facilities, but albeit with a glaring and ironic error in judgement: there’s no available parking for taxi drivers on street immediately outside on the 22nd Street off 7th Avenue, where the club is located. It’s also indicative of the kind of farce being played on medallion taxi drivers for a long time now.

While city officials and Marblegate Asset Management – who facilitated the opening of the taxi club – enthused about the club’s facilities at its launch last month, it’s clear that without available parking space, the club is not exactly going to be chock full of drivers who mingle, relax and work out, add some revelry and bonhomie to their strenuous work shifts.

Drivers, who wish to avail themselves of the club’s facilities, have to park on the adjacent 21st Street, a block away, with only half a dozen or so spots available there for parking.

When I visited the club early evening on a weekday, there was only one person inside the club, aside from an individual manning the front desk. I was not given access to the club. However, I could see new massage chairs, some video games stationed arcade-style, from my vantage point. I was told, in a section below the main floor, there’s also a gym, and a prayer room for drivers.

Outside, I asked a traffic policeman who doled out tickets to errant car drivers, if parking is allowed on the club premises – or rather the street outside, for taxi drivers.

He said: “No,” adding: “I’m being courteous to them for now if a car or two stop outside for a few minutes. They’re not supposed to park here.”

When I walked to the 21st Street, a yellow taxi driver of Korean-origin parked at the top of the relief line was dozing off at the wheel. He woke up when I tapped on his window. He was reluctant to give his name, but when queried, told me that he’d heard of the club, wanted to visit it, but they close at 7 PM.

“That’s too early, I won’t be able to go there,” he said. “Also, I can’t leave my card unattended here for too long.”

Road Rage

Walking on 7th Avenue last week, near 24th or 25th Street, I observed a case of road rage involving a yellow taxi.

A yellow cab stopped abruptly just past a green light on the outermost left lane, to pick up three passengers. A sedan following behind in the same lane, had to brake abruptly. The driver obviously didn’t take too kindly to what he felt was an egregious mistake by the cab in front of him.

After honking continuously to make his ire clear, he got past the yellow taxi as passengers clambered in. In an act of retribution, he braked abruptly once he was in front. It was a role reversal.

For long moments the car wouldn’t let the yellow taxi budge. Then he changed tactics. He moved a few inches, then again braked, to maintain the status quo. Traffic flowed on either side of them.

Almost, as if he had no fight left in him, or realizing the futility of it, and avoid further confrontation, the yellow cab suddenly took a left turn into a street, to continue his journey. The car ahead moved on.

(Sujeet Rajan is Editor-in-Chief of www.indiaoverseasreport.com Follow him on Twitter @SujeetRajan1)

(This story was produced as part of the Small Business Reporting Fellowship, organized by the Center for Community Media and funded by the NYC Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment.)